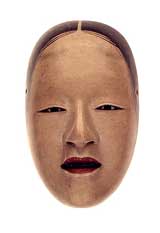

| Changing Face - Masks from the British Museum Gallery 4, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, curated by James Putnam and Stephen Feeke. 16 September - 1 December 2002. Masking is fundamental to notions of identity and society with an almost universal distribution around the world, in existence since Palaeolithic times. Today, the mask is a largely forgotten cultural artefact in the West, worn primarily for amusement or protection, and yet the seemingly harmless act of wearing a mask for Hallowe'en has a greater significance than it would first appear. The act of effacement and disguise creates a distinct psychological resonance. To suggest that someone is masking something suggests that they are hiding their real motivations and concealing the truth. The role of the mask is to invoke the extra-human, the divine or the metaphysical, and at the same time reveal something of the human condition. Wearing a mask can be for dramatic effect or can effect a dramatic transformation, changing the way in which the world is viewed by both the wearer of the mask and all importantly, by the audience watching the mask in performance. From the selection of artefacts for this exhibition, four general categories of mask can be outlined. - Masks used for dramatic effect, which disguise the performer and create a separation from the audience. - Masks that create a metaphysical transformation, and change the performer into some other being, creating an absolute separation between the everyday self and the masked entity. - Masks which are understood to contain divine or metaphysical powers. - Masks that have symbolic or metaphysical significance, but are not worn as coverings for the face. Selected images 1st image from top Wooden face mask, grasslands area, Cameroon, early 20th century, 1943. Af46. 1 This mask has the familiar distended cheeks associated with the city of Fumban, where it is interpreted as the ruler blowing blessings onto his people. Small holes around the extremity of the mask suggest that it was once covered with sacking to which polychrome beads would have been sewn. This accounts for the lack of finish and patina on the outer planes of the mask. This is not an area where it is possible to pass directly from the form of a mask to its function but this piece was probably associated with one of the palace societies of the Fumban kingship. 2nd image from top Mende wooden helmet mask, Sierra Leone ,early 20th century, 1956. Af27. 18 Masks such as this are often known as bundu masks, named after the enclosure where girls are kept during initiation into the Sande society that regulates female behaviour and interests. This is one of the few masking traditions in Africa where women actually wear masks, an activity otherwise limited to males. Even here, masks are still made by male smiths. The iconography of such works usually includes a number of elements representing an ideal of female beauty, with glossy skin, small facial features, decorative hairstyle and folds of fat at the neck. 3rd image from top 3/ Egyptian Mummy Mask, gilded cartonnage, (Greco-Roman Period) c.late 1st century BC-early 1st century AD, EA 209472 Mummy masks were worn over the wrapped head of the mummy. They were principally used to protect the deceased’s face but could also act as substitutes for the mummified head should it be damaged or lost. Egyptians believed that the spirit or ba survived death and could leave the confines of a tomb. The mummy mask therefore provided the means for the returning ba to recognise its host – whose face was hidden by layers of bandage – and it is therefore odd that mummy masks were rarely particularised portraits. Accordingly, this example has idealised features. The use of gold was connected to the belief that the sun god, with whom the mummy hoped to be united, had flesh of gold. 4th image from top 4/ Japanese Nô mask of a young woman, Japanese cypress with pigment,18th-19th century, Signed Norinari and Hôshô Daiyû , JA OA+7105 Nô theatre masks are the opportunity for very subtle expression in Japanese sculpture. The wooden masks are carved and then painted - in this particular case, the mask is whitened with crushed eggshell in an adhesive fluid. Finally, the hair and features are painted. Present-day Japanese Nô performances adhere to the traditions established in the 14th and early 15th centuries and a number of standard masks are used in different dramas. A skilfully carved mask will appear to have subtle changes of expression depending on the way in which the wearer turns his head and the angle at which it is held. To read more about this exhibition visit The British Museum's web site. |

|

||

| Wooden mask from Cameroon. |

|||

|

|||

| Mende wooden helmet mask. |

|||

|

|||

| Egyptian Mummy Mask. |

|||

|

|||

| Japanese Nô mask of a young woman.

|

|||