| |

|

|

|

|

|

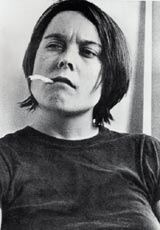

In conversation

with Sarah Lucas, January 2000.

Extract

JP: Freud has had an enormous influence on our attitudes towards sexuality and has revolutionized how we think about ourselves. Certainly his great writings, like ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ were the result of much self -analysis. I suppose, in a way, Freud as a person has become almost inseparable from his writings, how do you feel about your particular fusion between self and art?

SL: I’ve never been that keen to separate the person from the work, in fact I always wanted making art to be really close to myself. It suddenly struck me when I was first starting out as an artist, how much attention people put into their appearance every morning. This is not necessarily a vain activity and the result may not be glamorous. You might get up and put on your jeans and think, these jeans just look shit, or the next day you might think they look good. You could wear them for a week and then suddenly think, these just don’t look right, I don’t know why I’ve worn them for a week or two years or whatever. These kind of decisions are going on in our minds all the time. I really wanted making art to be like that, natural, or something to do with how you present yourself.

JP: Freud was very interested in the whole area of gender ambiguity, the male and female element in every human being and developed ideas about masculinity complex and penis envy. You certainly tend to come across as rather defiant and masculine in your self-portrait series.

SL: I suppose I’ve always worn the same sort of clothes, like jeans and been kind of boyish before I was even into art but I don’t think I consciously intended to look masculine. In still images, maybe I look more masculine than when I’m moving about. The first self-portrait I made with me eating a banana started out from something that I thought would be funny but I didn’t necessarily intend to make an artwork out of it. I just took the pictures and then one of them was really really strong and it turned out that I looked quite masculine, in fact people might not know whether it was a boy or girl. If I had been standing there in the nude or with make up on, looking girlie, it would have looked like any other picture of someone with a banana that you might see in a porn mag or a Sunday newspaper. But it was the fact that I wasn’t looking like that which gave it its strength, I sort of recognized that.

JP: What do you think about the direct or blatant sexual associations in your work as opposed to the kind of hidden, Freudian type symbolism.

SL: Well I think there are still layers of meaning and there might be a lot that’s hidden. I feel that one of the reasons why the directness can be said to be provocative, is not because you necessarily know precisely what’s meant which is what happens with the self-portraits. Because their gender’s sometimes ambiguous, you’re not quite sure what’s intended, that gives them power, so its still to do with hidden things. But on the other hand I think the

directness gives people the way in. I like to be direct, partly because its audacious and honest, both of which I like and also because I think it makes the work much more accessible on more levels, to more people.

JP: What do feel about this tendency for people to disregard the significance of the sexual instinct?

SL: I think that’s completely stupid, I know that from my own experience. All living things, not just animals but also plants, are entirely sexual, as Freud recognised and it seems amazing the lengths people go to to deny that. Like when you’re a teenager you go on a sexual quest for better and better sex or for an orgasm in some cases, and then for more liberated sex as if that’s somehow the answer to the problems.

JP: Do you think that the way that people appreciate your work is linked to that slight embarrassment or repression about open sexuality.

SL: Yeah, I do definitely. It’s not that people are necessarily repressed but I think the embarrassment thing is significant. For example, if you take those early works I made from the pages of ‘The Sunday Sport’, where I blew up the centrefolds. When you see them sitting reading a newspaper on a train its a very discreet activity. Viewing them in a gallery is a very different thing especially if your walking around with your family or among others, perhaps, people who you don’t know looking at this stuff giant-sized. I mean that makes you automatically very self-conscious but I think that embarrassment effect gives the work a lot of power.

JP: What do you think about Freud’s view that many obsessive activities are often sexually driven?

SL: Talking about this whole libido thing, I suppose there is this obsessive activity of me sticking all these cigarettes on the sculptures. Part of the thing of using cigarettes came out of the the idea of making things out of matches. I was thinking the other day about prisoners. I like the idea that art can’t be taken away from you, even if you have only poor materials. So if you were locked away as a prisoner, there’s still some things you can do and you can formulate and visually manifest and I like that very much. Yet when you think about it in a different way, if you were a prisoner all that kind obsessive activity could be viewed as a form of masturbation, it is a form of sex, it does come from the same sort of drive. And there’s so much satisfaction in it, in the same way that there is in the subtler aspects of sex, in that you’re hitting the mark.

JP: Do you find Freud particularly relevant to what you are all about and do you feel that this occasion of showing your work in his house rather than a conventional art gallery is significant?

SL: From what I know I suppose it’s all relevant. I think that stuff Freud wrote about jokes and their relationship to the unconscious is totally relevant to me. If everything happened through premeditation you wouldn’t get anywhere that you didn’t know about before you started. When you’re making work a lot of the best things happen that way through those kind of slips. And I do see my work interacting in some way with his house. I suppose its essentially the whole Freudian thing which is most paramount, both the sexual dimension and the hidden elements. I think people can go and look at the work there because they’ve got all that stuff about Freud in mind. They can actually begin to see some of the broader aspects of my own work that they hadn’t necessarily considered when placed in this context.

|

|

|

|

Sarah Lucas

|

|

|

|

|

|